The last thing I wrote was a review of the new Patricia Grace collection, which was a) fairly lengthy, and b) at least somewhat well-constructed. So, I thought it’d be a good to blow out the cobwebs with a review that’s a) short, and b) messy.

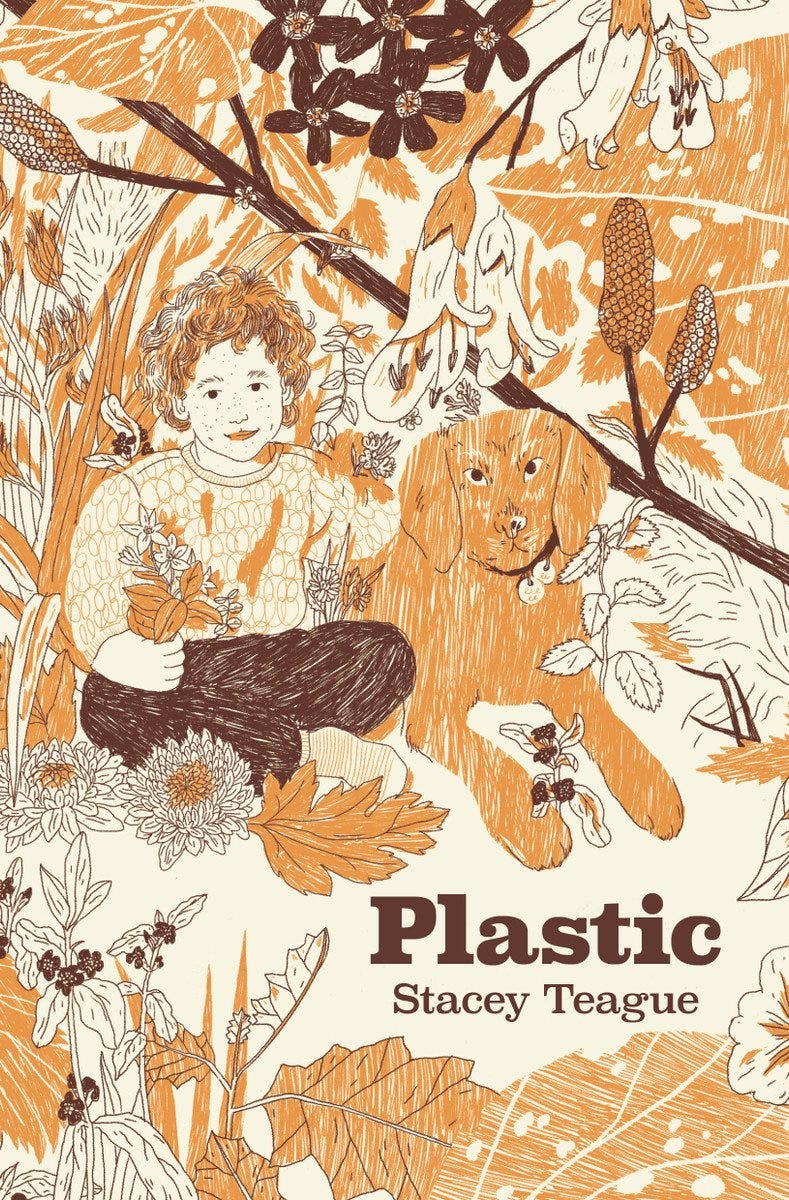

Stacey Teague’s new collection Plastic is the sort of collection that people will probably think is a debut (I’ve seen at least one article have to make a correction). It’s not a debut, but I can see why people think it is; takahē, Teague’s first collection, was released a decade ago, and to the best of my knowledge is hasn’t been available physically for a while.

As a side note, you can pick up a digital copy of takahē through a ‘pay what you want’ model here: https://thescrambler.com/digital/index.php/product/takahe/

I could be wrong here, but Plastic feels like a collection that has been a long time in the making. There are disparate sections – some prose, some ‘spells’ – that read like they could have been the seeds of larger projects at one point. Even individual poems burst with ideas, optimistically tossing out images like birdseed. Its title obviously refers to the notion of the ‘plastic Māori’, so there’s a bit of stuff here concerned with disconnect from whakapapa/tikanga, but I really enjoy the variety and vibrancy of this collection.

In lieu of any proper thesis here, I just wanted to share some thoughts about my favourite pieces in Plastic:

HOKI -

I’ve said in the past that some of my favourite recent prose is contained within poetry collections, and I could lob some similar praise here. There’s something so appealing about the ‘easiness’ of prose paired with poetry’s desire to just establish and live in moments for a while.

One thing I really like here is that the approach to dialogue is very fluid and ambiguous. Teague goes beyond the fairly standard method of not punctuating dialogue; we get these moments where dialogue is ‘set up’, but what comes after is not necessarily even dialogue.

For example: ‘Sitting with Mum while she is sunbathing, I ask about her father. He was an alcoholic, never saw him much.’

Is this something being said by Mum? Or is it something known by the speaker, going unsaid by Mum? These little moments of ambiguity make for some interesting character moments, where the dynamic is uncertain.

DREAMWORK -

‘Dreamwork’ is a fragmented tribute to Mary Oliver’s collection of the same name.

The poem is structured like recounts of various dreamscapes, but there’s an uncertainty to these dream snippets. When/where do these narratives enter dreams? Part 4 questions whether the speaker is dreaming at all.

I particularly like the ambiguity of whether the speaker is actually accused of ‘not being Māori enough’ or if that simply happens in a dream. Not to undermine the possibility of that happening – I’m sure it does – but it’s also a feeling that often manifests internally, and I like that this may suggest that.

Lots of strange, surreal moments: ‘waking up alone in an absence of blood’, ‘in the morning a garden / is growing in my spine’, ‘a house with two doorways / the young moon on its back’.

BLUE HOURS -

I like how ‘Blue Hours’ uses the colour blue: this simple colour motif that has an ineffable metaphorical quality. There always something appealing to me about stark, simple imagery being used in a complex way.

For example, the speaker coughs up a (figurative?) feather on ‘a blue morning’, they live in ‘this blue version of a life’, they wake to ‘a bluish stain’ on their bedsheets’.

For some reason I’m reminded of the Blue Fury in Janet Frame’s Living in the Maniototo.

LOVE LANGUAGE -

There’s something of Tuwhare’s ‘girl in the park’ here (a poem that I will write about at any opportunity it seems) in ‘Love Language’s crystalline, wide-eyed wonder: the ‘big air’, seeing one’s life ‘as big as a movie screen’, touching a poem ‘in a romance way’.

A lot of my favourite poems seem to deploy almost-too-simple language but in a way that feels unusual. It’s a fine line, but ‘Love Language’ walks it.

TE PŌ -

This one’s the highlight of the collection for me.

I love poetry that plays with multiple threads but never quite brings them together. Here we have spiritual, suggestive opening and closing sections that sandwich a more straightforward segment where the speaker recalls a girl called Te Pō who died after falling onto concrete from a tree.

KURANGAITUKU -

The speaker reflects on seeing a play in primary school about Hatupatu and the bird-woman. They recall the sad image of Kurangaituku ‘sprawled out and lifeless / on the lacquered brown floors / of [their] school hall’ – ‘nobody mentioned her name’.

Like Whiti Hereaka’s recent novel, this poem is about Kurangaituku’s reduction to a monstrous, nameless figure, about the ways in which such narratives can be renegotiated: ‘some say she abducted him / others say he was invited’.

TOKIKAPU -

I really like the no-nonsense, economical style of Teague’s prose. It makes warm images like colours swirling around a cup of tea, or the ‘greenest sea’ of surrounding hills, shine.

This is a prose piece about cultural reconnection, and I think it captures that quiet wonder with which one is rediscovers their whakapapa, their whenua. There’s a hard-hitting, understated-ness to lines like: ‘I grew up in a Pākehā world, nobody taught me how to be Māori. This is not unusual, but no one talks about it.’

She looks over to me and says, in her small silvery voice,

Those are your tūpuna, honey.

Omygosh I need this book after reading this. Thank you! 🙏🏽