An Englishman, an Irishman and a Welshman walk into a pā

A look at Tina Makereti's new collection of essays

Well…I’ve had a bit of a break from Substack, but I’m back and ready to hit the rest of the year hard. It’s currently the school holidays and I’ve been writing recently - I look forward to sharing new pieces in the coming weeks/months!

This is a review that was originally published on Newsroom’s books section Reading Room.

The ‘personal essay boom’ may not be entirely over, but we’re surely in the fallout zone by now. It seems fitting then that Tina Makereti’s essay collection This Compulsion in Us essentially opens with a re-justification of the essay as a form. “The great pleasure in creative nonfiction,” she writes, “is the paradox that confronts me every time I write”. Paradoxes, conflicts, and contradictions are recurring motifs throughout this collection, and I can’t help but see Makereti’s work as a response to writers who might use the essay form as a blunt tool to reduce complex issues to digestible ‘takes’. She’s a teacher of writing, after all, and in one essay she tells her students (and the reader) that writing is an enactment of tension; the fact that that essay ends with a postscript and a post-postscript is the perfect example of how this attitude manifests in the form of the collection itself, with new questions arising and spilling out over the edges.

And if there’s any form of literature that benefits from being a little overlong and imperfect, it’s the essay collection. I’ve never really understood the tendency of marketers (and reviewers) to want to sand down disparate collections of nonfiction writing into cohesive ‘statements’, and the best books of essays defy easy categorisation. The first thing I noticed about This Compulsion in Us was its sprawling scope; I don’t know if it actually collects every essay written by Makereti over the past two decades, but it sure feels like it. In addition to fully fleshed-out pieces on history, te ao Māori, and writing (to name a few of the issues that interest her), we also get oddities like ‘funny little ugly baby’, a one-paragraph piece of flash fiction. These previously published works are punctuated by what Makereti calls “moments of memoir” written between 2018 and 2024 – smaller, less-structured vignettes that are dated to periods across the author’s life.

I’m ashamed to say that before reading this collection, I wasn’t aware of how good a writer of nonfiction Makereti is: the best essays here are complex, thoughtful meditations, and surely some of the finest Aotearoa nonfiction of this century. She does her best work when embroiled in conflict and contradiction. In ‘Twitch’, she considers the divide between the internal and external worlds, asking, “How do we know our place in the universe?” The essay is one of many examples of Makereti weighing up all sides of her ancestry, as she lovingly evokes Māori cosmology by way of the Big Bang.

In doing so, she challenges the clean divide that has been erected between our internal and external lives, suggesting that the secret to traditional Māori understandings of the universe may have lain in their ability to exist in the uncertain spaces between:

“It is possible they looked inward as often as out, travelling the complex pathways of the mind and spirit, touching ancient wisdoms about our origins only dreams can offer. And, in the darkness with only natural light from the Milky Way to see by, they began to understand what lay behind the stars, what went before them, the place of potential, Te Korekore, with Io twitching into life.”

This fascination with those who live between worlds is vividly explored in the essay ‘An Englishman, an Irishman and a Welshman Walk into a Pā’, which I’d say is the standout here. It’s a piece about cultural reconnection, but Makereti complicates the standard roles we often force historical figures into. In particular, she gets caught up with her Pākehā ancestors who adapted to aspects of Māori life, and is drawn to these ‘Pākehā-Māori’ who existed in the space of transition before colonial dynamics solidified: “Did the absolute insistence on a ‘European’ identity come much later in our story than we like to think?” Makereti characterises the potential of our literature as the ability to tap into “the convoluted mass of stories from our collective past” and reject easy narratives. These, I think, are the strongest moments in This Compulsion in Us. There’s something inspiring – and straightforwardly satisfying – about this vision of a genuine post-colonial literature that honours the complexities of our past, present and future: that is, “the extraordinary mix of language and narrative and metaphor that could only take root in this one place on earth.”

Makereti likewise takes every opportunity to position these essays within an even wider paradoxical milieu: the spectre of climate change and societies about to step into a new age (willingly or otherwise). “As well as writing to you from a very specific time and place,” she writes, “I am also writing to you from an apocalypse.” A collective dread hangs over This Compulsion in Us; I’m reminded of the extent to which so much Cold War-era literature was dictated by the threat of nuclear war. In fact, Makereti draws this connection herself, professing that she is “a child of the nuclear 80s, and the end of the world haunts [her] every step.” This dynamic is, I feel, reflective of what I enjoyed most about her excellent 2024 novel The Mires, which focused on a small cast of characters existing in one small corner of a near-future sort-of-dystopia. It also leads to some darkly funny moments, such as when the author states that she’d never be one of those people who gets interviewed after a murder and says that she never suspected anything: “I have imagined everything,” she writes bluntly, “I have suspected everyone. There will be no surprise tragedies, for I have lived them all.”

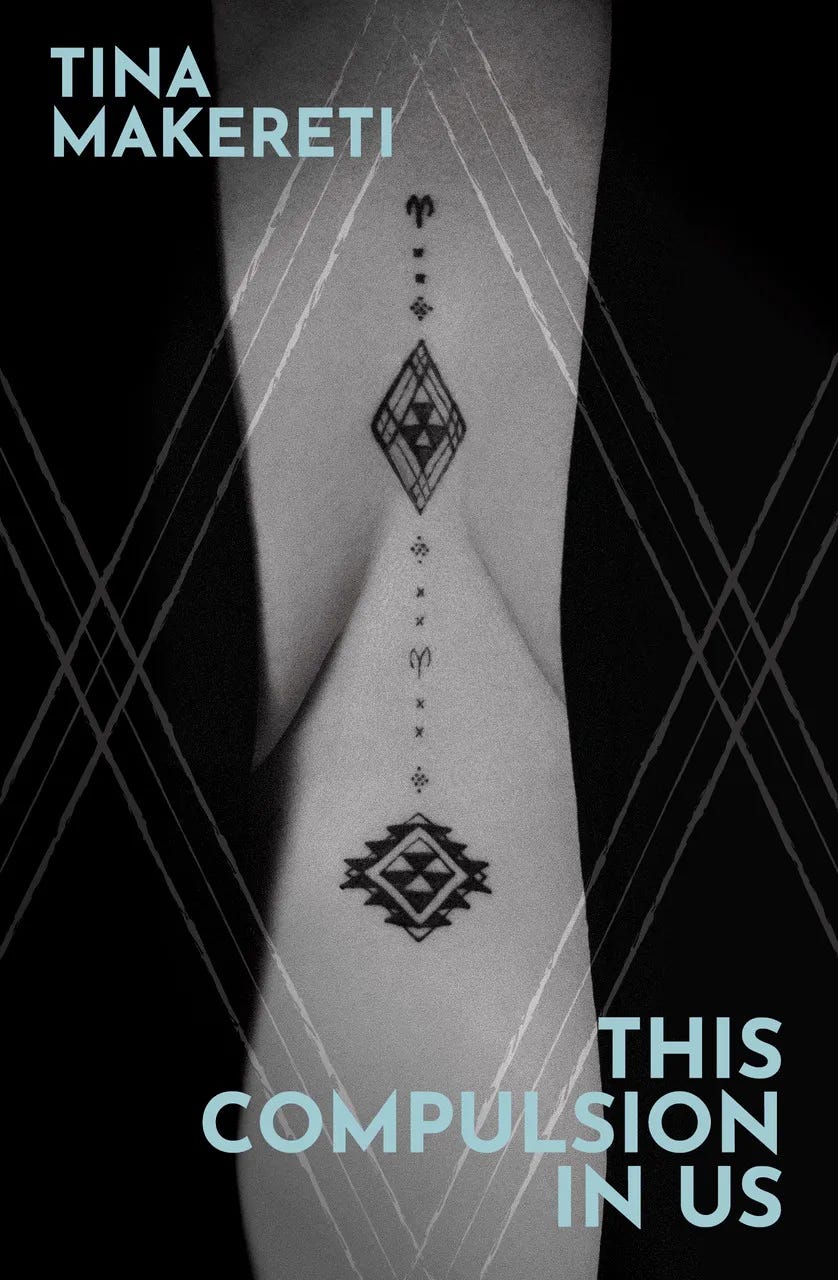

An Ebony Lamb portrait of Tina Makereti

With these essays often expanding their scope to planet-wide concerns, what is the effect of these ‘moments of memoir’ that are interspersed throughout This Compulsion in Us? For one, “more texture and shape” (Makereti’s words, and she’s right). The best nonfiction writers have range, and these autobiographical cuttings have a looseness, a relative formlessness, that provides a foil for the structural ambitions of Makereti’s best essays. She quite often simply strings together a series of thematically linked headings and seems to enjoy these moments of abruptness. At its best, the interplay between the essays and ‘memoirs’ serves to enrich our understanding of Makereti as a writer, and the things that radiate from the collection’s core: her relationship with her father, a complex – often paradoxical – relationship with te ao Māori, the surprising moments of clarity gained when a stranger in another’s culture.

And yet, the collection is unusually guarded, which becomes a larger issue as the topics get more personal. I appreciate the unadorned style used in many of the ‘personal’ essays, but many lack specificity to the extent that I struggled to connect in the way that the pieces seem to want. We read that the author connected with whānau through dark humour, but we don’t really see it. What seem like important figures in her life are often drawn in the vaguest possible terms. Makereti feels unsure about which facets of her life to display here. That’s not just speculation on my part either – This Compulsion in Us is open about its blind spots, especially when it comes to the author’s father. In one particularly frank moment, Makereti admits that “there is so much [she] can’t stand to put down [on the page]”. Elsewhere, she writes more cuttingly about the version of her father that roams these pages: “I still censor what I write down. There are some truths I just won’t get into, repeat, go over.” You might imagine that this approach would – as one piece here suggests – let Makereti’s father off lightly, but to be honest I actually found the opposite. Almost all of what we learn about him is negative, and the collection is so hesitant to divulge details that could contextualise his actions. At one point, Makereti meets a relative at a family gathering and he mentions her father’s life story – but we’re left in the dark as to what that ‘story’ contains.

A few of these essays use a technique where they open with an unnamed subject (in one case her father, in another a dog) and carefully build towards the naming. I wonder if Makereti intended the collection to function similarly, on a larger scale: for the blanks to be filled in over the course of multiple, often-disparate essays. If so, it doesn’t always work for me, particularly in the collection’s latter half. As the concerns get larger, the writer gets lost at times. The Mires balanced these issues with more grace: the lives and relationships of characters in that narrative are given weight, even as their desires come up against the pressures of a burning world. When I’m several personal essays deep into a writer’s life, why do I know so little about them?

But then, as if responding directly to my misgivings, This Compulsion in Us’ final piece – a postscript written in 2024 – decides to bare a little more of Makereti and her relationship with her father (if not all of it). This late addition is startlingly blunt at points – “It’s a truly awful sentence to write, but there were many times I wished for my father’s death” – but it also feels like the moment when the collection’s personal writing truly embodies the uneasy paradoxes that define Makereti’s best fiction, the tension that she evokes throughout these essays in other ways.

“Dad was always perplexing,” she writes when recounting a visit to her father with her daughters (who hadn’t seen him for years):

“This was a bit of a worry, given the way he treated me, and we all prepared ourselves for the worst. Would he say something painful, racist, insulting? But he fawned over them. ‘Isn’t she beautiful?’ he said. ‘Like a supermodel.’ He was delighted, and delightful with them. He was the best version of himself he could be that day, even offering his queer granddaughter his bed so that she could come and visit with her partner. ‘I’m not prejudiced!’ he declared.”

Earlier, Makereti writes, “If we’re doing it right, most days we’re not going to know what’s going to happen.” The late inclusion of this postscript seems to suggest that the author’s vision of what this collection ‘is’ shifted over time – that the writing entered territory that required a more fitting conclusion that leaves less unsaid.

In this sense, This Compulsion in Us is more open about its own construction than maybe any other book I’ve read, and I don’t mean in the knowing metafictional way in which most authors meditate on their craft. I’m impressed by Makereti’s openness about her own artistic insecurities – as such, the moments when she begins to push through these barriers feel vulnerable and honest in a way that I don’t often associate with the finely tuned ‘modern personal essay’. It feels like I’m seeing, in real time, one of our most important living writers enter a key state of transition; her writing had, in some ways, been holding back, and the collection is, on some level, about the desire to push one’s art into uncomfortable personal territory. Perhaps this honesty shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that extensive psychological exploration is one of the hallmarks of Makereti’s writing. Much of her best fiction is defined in part by its ghost-like wandering voice that can dive into minds and stories at will. I’m excited to see what the revelations reached here will mean for the fiction to come.

And ultimately, this is what I wanted – a sprawling essay collection that’s far-reaching enough get a little messy and genuinely introspective. It would have been pretty easy to strip This Compulsion in Us to about half the length, make it a lean, mean collection of essays about the kinds of topics that people who buy essay collections like to read essays about.

But that collection wouldn’t have even attempted to embody the ‘paradox’ that defines Makereti’s work, which she grapples with in the opening essay:

“… as I attempt to find more precision and more elegance, more accuracy, as I try to pinpoint any one true thing, I am often frustrated. To solidify something in words is only to omit that aspect of it which defies definition, the ‘nothingness’ which underlies the thingness. It is in meeting my failure on the page that I come into contact with that which underlies all creativity and creation: Te Kore…”

Does This Compulsion in Us succeed in this? Could it ever? Probably not, and I imagine Makereti would agree. But I’ll happily settle for an excellent collection of essays that questions its own craft so openly, and embraces a messy, paradoxical sort of potential.

Tēnā rawa atu koe, thank you Jordan for an insightful reflective consideration of this collection. I have long admired Tina Makeriti and will continue to read her creative works.

I liked that you said this: 'a sprawling essay collection that’s far-reaching enough get a little messy and genuinely introspective.'

The commercial pressure on writers to reach a market and entertain the market is, well, commercial and commercial imperatives constrain free-range thought. The chickens can never come home to roost if they are confined in a battery shed with artificial light.

I, for one, (and I hope I'm one among many) demand that writers take risks; that they grope through the darkness rather than turning on the artificial light. I like the journey to reach the dawn. (As I write those wild geese are calling as they come down from the mountains, scraping their sound over the wetlands and up to the moon).

I will keep reading this author, just as I will keep reading your finely wrought reflections on Māori literature, a rich field of work.

I haven't read this one, and didn't persevere with The Mires. However, in I've just read Lawrence Patchett's The Burning River 2019 which I was really impressed by. Have you reviewed it at all?