JOY COWLEY AND ARAPERA BLANK ON THE BONE PEOPLE

The Listener's 1984 dual-review of Keri Hulme's landmark novel

The NZ Listener’s May 1984 issue featured a dual review of Keri Hulme’s the bone people, with separate takes from both Joy Cowley and Arapera Blank. I’ve heard these reviews referenced quite a few times (like in this excellent piece: https://medium.com/spiral-collectives/the-bone-people-f73c01ce7684), but have never read them in full. Today I found a cut-out of the original page, so in the spirit of making myself useful, I thought I’d type them up for my subscribers (and the internet at large I guess?).

So yeah, not a real post today (as in written by me), but I hope you enjoy these historic responses to the bone people.

‘We are the bone people’

I HAVE BEEN waiting for this novel, watching the earth, knowing that it had to come. We all knew it. Someday there would be a flowering of a talent which had not been transplanted from the northern hemisphere, which owed nothing to the literary landscapes of Europe or the film sets of California, but which would grow – seed, shoot, roots and all – from the breast of Papa. Now we welcome it with a glad cry of recognition.

We have known this book all our lives. The pages are textured with the rough and smooth of our own being; the sounds of wind, sea and deep earth music have always been with us; the words have the smell of our small births and dyings, dyings and births. We are the bone people. Keri Hulme sat in our skulls while she wrote this work, and yet, in spite of the instant recognition, none of us could have written it, for it is uniquely hers.

I am struck by the range of people who inhabit the bone people. The novel is as wide as a city railway station where the main characters wait for the train which matches their tickets, while the rest of the population passes through, each person adding his or her own small journey to the main line. No character is called out of coincidence or forced in by convenience. Each moves easily in her or his space which is part of the whole.

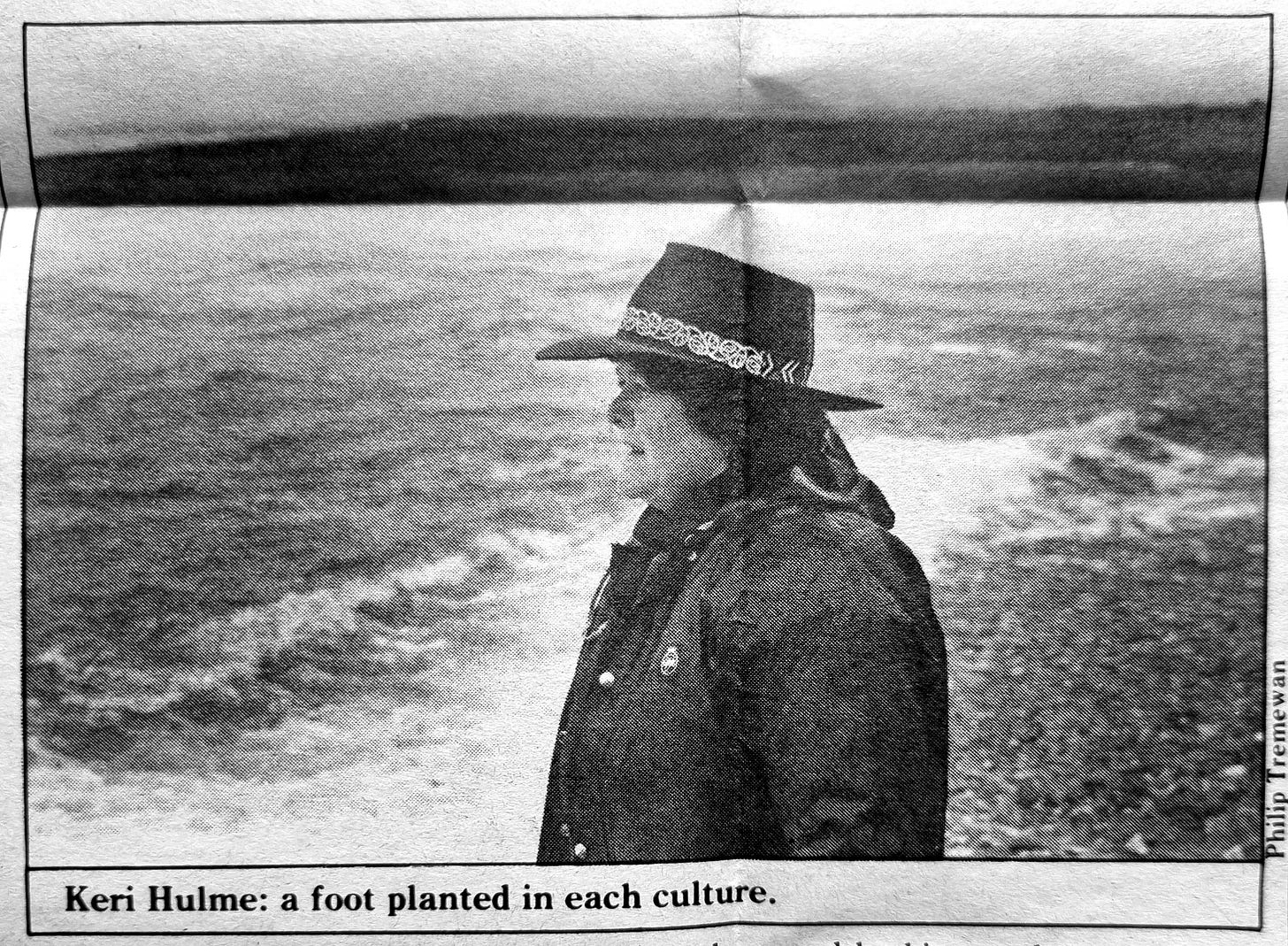

The range of multicultural experience is equally wide and presented with similar ease. An Old Testament of Maori mythology is woven through space-age technology, fusing dream with fact, and fiction with truth. Again, nothing is forced. Situations fall logically and inevitably in a natural chain of cause and effect. Large tragedy is never far from large humour; love and violence are complementary, beauty slides into ugliness to emerge again as beauty. Keri Hulme stands with her main character between two cultures – a foot planted genetically, traditionally, in each – while at the same time maintaining her independence as an artist.

In another novel, the large chunks of description, sometimes encyclopaedic, could seem excessive. In the bone people these passages have the feeling of rightness, for they belong to the main character Kerewin who gathers the glittering bric-a-brac of the world into her life with enormous appetite and then, unable to digest it as fuel for human love, spews it out again in torrents of words, pictures, music. Kerewin the artist seeks to create, beyond the flesh, all that flesh desires. Many of the descriptive passages are painted in a sort of frenzied displacement activity, pictures thrown into the air in hasty denial of love, weakness, self-pity – as when the small boy Haimona (Simon) makes a claim on her heart.

. . . He holds her hand more tightly, sweeps his eyes from her wild flurry of hair down to her bare feet, what is wrong? What is wrong? Can I help? up to the odd pendant that hangs, like his label, in the middle of her chest. Only her pendant is made of a blue stone, carved like a complex open knot.

“That,” she says, after tracing his gaze, “is a sort of Sufic symbol. Worked quite cunningly in turquoise. The circle is silver.”

She takes her hand away to hold it closer for him to see, poised between her forefingers.

She doesn’t like holding hands.

He is amused.

“Okay,” mistaking the small shark grin, “so I gloat too much on things I like. Inside Gillayley, before I change my mind and send you away.”

“Not really,” she says, inside the hall. “I suppose it’s really a compliment that you want to stay, eh. But only God knows why,” and she sighs.

She stands at the bottom of the spiral and chants.

“There is both amber and lodestone.

Whether thou art iron or straw,

thou wilt come to the hook.”

She stops, frowning at the silent crucifix.

“Why should that come to mind?” Over her shoulder to the silent child, “From the Masnawi by a poet called Rumi.”

Jalal-uddin the Sufi.

Ah hah, back to the Sufic knot. Not to mention fishing. Quid est.

In the living room, he looks round and sighs. Then he turns to her and hunches his shoulders. He stands there staring.

The silence, o my soul, is getting awkward again.

For the boy’s stepfather, Joe, there is no such diversion. Experience rushes headlong into emotion and action, at times defying reason.

“Aue, aue . . . okay tamaiti, okay . . .” he strokes Simon’s hair away from his eyes and kisses him. “Taku aroha ki a koe, e tama.”

All still, all silent, except for the sea.

They can’t hear Kerewin’s breathing even.

Joe sighs.

“Eh, I don’t know why I hit you,” he says in a low voice, talking more to himself than his child. “I’m drunk or I’m angry, I’m not myself . . .”

Then there is the boy, Simon Peter Haimona, the sea-child who does not speak. The three are inseparably removed from each other as the points of a triangle, Kerewin forming the apex. Only death and rebirth can unlock their positions.

YEARS AGO, an enthusiastic Australian critic tried to tell me how he felt on first reading Patrick White’s The Tree of Man. “He gave us ourselves!” he exclaimed.

I now understand what he meant.

Keri Hulme has given us – us.

- Joy Cowley

KERI’S NOVEL has the preciousness of a piece of “kuru pounamu” in its apparent simplicity of shape, because it is concerned with the universal theme of aroha. Yet, like the many shades of green that is pounamu, it mirrors all those facets of life, of creativity, that make writing truly exciting! The language, the feeling in this humane story, pulsate with the rhythm of the sea around us that is Aotearoa; reverberate with the music and drama of the marae that is oratory, the waiata, and the pounding feet of the haka.

The boy, the piece of flotsam, is Pakeha. But he is also Maui-Tikitiki-O-Taranga, the potiki, the youngest child of Taranga who rejected him because he was born prematurely on the sea-shore; the Maui who was fashioned and formed by the seaweed, squabbled and screeched over by sea-gulls, cradled in the deep, and rescued by his grandparent, Tama-Nui-Te-Rangi. The lifestyle of this boy is that of a Maui – impish, devilish, bloody infuriating, bloody-minded and wanting to be loved. His behaviour toward those who care about him is without ambivalence to people who have known the pain of aroha. He is reticent in his responses as to why he is so loyal to the very person who almost kills him, because this person, despite his violence, loves him. He is impatient with the woman who finally, though gradually, accepts him, because she tries to reject love. And he wants to unite these two lonely people by unknowingly allowing himself to be subjected to violence, dishonesty and what I would call “The-Art-Of-Getting-On-With-People-Who-Don’t-Know-What-I’m-Screaming-About”.

The man who breathes life into the piece of flotsam is Maori, immersed in the spirit world of the Maori in stressful situations, and educated in the world of the Pakeha. He is what aroha means to those of us brought up in the traditions and customs of the Maori world. He is harsh when he loves. When his foster child oversteps the boundary of propriety, he almost bashes the child’s brains out. Then he is filled with remorse and haunted by kehua. He is ashamed that the woman with whom he wants to share this child might not want him because of what he has done. He drinks too much. He even attempts suicide. And yet for all his failings he is salvageable because he loves this broken piece of humanity that is Simon P. Gillayley. Is this man of wayward moods Tama-Nui-Te-Rangi? The ancestor who rescued Maui from the deep?

The woman into whose deliberately private world this piece of driftwood has intruded is a mixture of both worlds – Maori and Pakeha. She tries to opt out of what is painfully close to her bones by isolating herself in a tower-like structure on a lonely sea-shore. But the insistent drum-beat of suffering surfaces when Simon P. Gillayley crashes into her seashell of privacy, broken bones and all! Is this woman Tama-Nui-Te-Rangi? Is she Hine-Nui-Te-Po?

Maybe she is both: lovable, loving, caring, rejecting love. She fears loving because it might not be returned – might not last. I think she wants to be someone who gives, but does not want the pain that givers are the inheritors of.

The title the bone people is quite apt because the story is concerned with the spiritual and emotional needs of a whanau, and the demands placed upon it by the common bonds of descent, heritage and environment. That the central character, the boy, is Pakeha makes the title even more meaningful. The writer has grasped the reality of the New Zealand situation, and that is, that Maori and Pakeha are sharing the heritage of the tangata-whenua – those people who fed, clothed and housed strangers on their shores.

Keri Hulme, tena koe, whanaunga o roto o Ngai-Tahu, o Ngati-Mamoe! You have the nerve to leave the reader with the heart-ache of responding to the crying of many aching bones! What a dilemma! Ah! But what a wonderful piece of art you have created!

May I take the liberty to help those readers who are in doubt?

Haramai whanaunga,

Whakamamatia nga

Mauiuitanga e ngau nei,

I oku koiwi.

Tu mai Hine-Matioro!

Na to taina,

Na Arapera o te Tairawhiti.

Come relations,

Lighten the burdens

That bite

into my bones!

Stand up, wonderful woman!

From your younger sister.

- Arapera Blank