MĀORI LIT ON SCREEN: BIG BROTHER, LITTLE SISTER

The first in a new series of posts looking at screen adaptations of Māori lit

Well, it’s been a while. I’ve been really busy with both my day job and some creative projects - like putting together the third issue of the lit/art journal Pūhia, which will be revealed very soon. But I’m back now and ready to get this blog properly cooking again for 2025.

An idea I’ve had for a while is sitting down to watch and write about every screen adaptation of a work of Māori literature. ‘Māori Lit on Screen’ will be an ongoing series that I’ll come back to every now and then, until I’ve eventually covered them all!

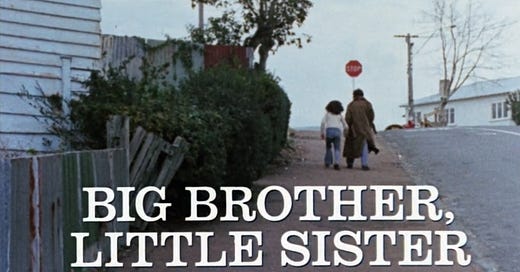

BIG BROTHER, LITTLE SISTER [1976] dir. Ian Mune / adapted from a story by Witi Ihimaera

Ian Mune’s TV short film adaptation of ‘Big Brother, Little Sister’ is the logical starting point for any discussion of Māori literature on screen. It’s not actually the first screen adaptation of a Māori work of fiction – and I’ll talk about that in an upcoming post – but it certainly feels like it.

‘Big Brother, Little Sister’ was part of Roger Donaldson and Ian Mune’s anthology series Winners & Losers: TV-length screen adaptations of Aotearoa short stories, based loosely around the unifying concepts of success and failure. It’s a landmark series, and a great idea; I’d love a modern equivalent that could draw on the best short fiction of recent years.

And yet, the short film undeniably carries some pretty ugly baggage. It’s the first truly noteworthy screen adaptation of a Māori short story, and it’s about domestic violence (and very little else). The description on NZ On Screen even opens by remarking that the film was made ‘almost two decades before Once Were Warriors’ (the film around which every other Māori film must revolve, it seems). In addition, ‘Big Brother, Little Sister’ (along with the rest of Winners & Losers) was – to the best of my understanding – a favourite with teachers. On one level, this is fitting: right from the start, Ihimaera stories have thrived in schools. On another level, the thought of these stark scenes of abuse, against the dilapidated walls of the central run-down villa, beaming into classrooms makes my stomach turn. Teachers often struggle to contextualise stories of Māori suffering in today’s classrooms; I can’t imagine how this film was presented to the Pākehā middle class of the 1970s. There were far more ‘filmable’ Ihimaera stories in 1976 – what exactly led Donaldson and Mune to this one?

It'd be easy to write the film off on this basis alone, but such a dismissive reading is complicated by the genuine respect and taste that Mune applies to the subject matter. It’s grim, but it’s never actually all that violent, and the worst stuff happens out of frame. Like the original story, the narrative focus is on the quiet strength of the two young leads.

My initial uneasiness is also complicated by the fact that ‘Big Brother, Little Sister’ is actually pretty damn good.

Yes, the harsh low-budget atmosphere results in some awkward moments. But you also get striking stylistic decisions that I just can’t imagine seeing in a more contemporary piece of local television. I love the abrupt editing, particularly as Mune cuts bluntly from close-up shot to close-up shot, with characters often staring down the lens. This confronting ‘realness’ is also apparent in the moments when the film takes on a near-documentary style, particularly the shots of the city’s grey streetscapes that punctuate Hema and Janey’s journey to the train station. My favourite aspect of the original story (and much of The New Net Goes Fishing as a whole) is Ihimaera’s rushing, lurid descriptions of urban Wellington, and Mune honours that with his own visual language (although I think this was filmed in Auckland?). Ihimaera’s story was, I think, all the more effective as a contrast to the rural settings that had dominated most fiction written by (and about) Māori up to that point – The New Net Goes Fishing opens with a story about a whanau moving to the city, and I think that explicit moment of transition is meaningful. I wonder whether that dynamic was apparent to viewers in the mid-1970s.

I also have to give praise to the performances of the young leads, Dale Williams and Julie Wehipeihana as Hema and Janey respectively. Wehipeihana especially excels under Mune’s direction – we get these long, tense close-up shots that seem to scrutinise every slight shift in expression. And Williams is great; he carries a narrative that could easily turn meandering. Don Selwyn also puts in a good performance as the abusive Pera, and I think what I find most refreshing about his characterisation is that he’s not the staunch, masculine Māori abuser that would take hold in popular culture post-Warriors. Selwyn plays the role with an uneasy sense of insecurity, which to me seems like a thoughtful depiction of a man who uses violence against his family.

Ultimately, after watching a few of these 70s-80s local television films, the thing that stands out most about ‘Big Brother, Little Sister’ is that there’s clearly real talent and vision behind the camera – and they knew how to use their budget and resources artfully. I love the film’s final moments, in which Hema and Janey are stranded on an empty train platform. There’s a great shot from behind the characters: train carriages rush past, and then stop, leaving this hollow black sky. The lighting almost seems stage-like, the kids spotlit in a dark, near-liminal space.

It'll forever be tied to real concerns about how Māori stories of abuse are created, adapted and consumed – the director even went on to helm What Becomes of the Broken Hearted? – but taken on its own terms, ‘Big Brother, Little Sister’ holds up pretty well, I’d say.

It’s even available to watch online at NZ On Screen if you feel like checking it out – would love to know what you think!