Hone Tuwhare’s No Ordinary Sun – the first single-author poetry collection by a Māori author – turns sixty in September. This should of course be a significant milestone, but I can’t help feeling that poetry collections exist in a very different world to novels and short story collections. Compare No Ordinary Sun to Tangi, for example: I can walk into most any bookstore and buy a shiny new anniversary copy of Witi Ihimaera’s first novel. However, economic realities mean that something like No Ordinary Sun will likely never be re-published on such a scale (unless one counts its inclusion in a massive volume of ‘collected works’).

As a result, No Ordinary Sun feels more like a historical artefact than many other significant works of Māori literature – a footnote, not something that a casual reader might actually sit down and read. While that sort of reputation has its value, I’m always a little wary of reducing works of art to mere milestones. When something becomes ‘important’, that importance can often smother its other qualities, what that work actually is.

But No Ordinary Sun does feel somewhat out-of-step with other foundational works of Māori literature. It was published nearly a full decade before Ihimaera’s earliest books; stylistically, Tuwhare’s debut collection feels even older than that. In my American edition of Deep River Talk: Collected Poems, Frank Stewart’s foreword feels the need to highlight just how antiquated Tuwhare’s early poetry felt, even at the time, to many readers:

[…] the poems [in No Ordinary Sun] are clearly youthful and modest, formal and controlled [..] To an American ear, the style at this point is clearly British influenced, which means that the poems echo a high and somewhat elegant verse of an earlier time in England – in contrast to the disruptive, confrontational, and experimental verse being written in America in the 1960s.

Tuwhare would become far more experimental: his later collections are often surreal, silly, and anchored in his unique colloquialisms. No Ordinary Sun only contains hints of how far Tuwhare’s style would travel. For the most part, these are serious poems in more traditional forms – terms like ‘O’, ‘thine’ and ‘yonder’ are used unironically.

One poem here that foreshadows a more colloquial style is ‘Monologue’ (a title that suggests something a little more stream-of-consciousness). The speaker here is a factory worker who talks about their working conditions with a knowing matter-of-factness, and Tuwhare shifts his style to reflect this. In the foreword to No Ordinary Sun, R.A.K. Mason (Tuwhare’s long-time friend and supporter) spends quite a few words talking about the significance of the collection as a work of Māori literature; but he’s almost equally as enthusiastic about Tuwhare’s working-class status:

In these days when so much poetry is clouded with caution, sickness, weak cynicism, it is good to find a man seeing things with the clear vision of one who knows life by work, by hard work with his hands. I hope that many will welcome this book as I do, glad that the stuff of poetry can still be found in such store, can be given form by the pen of a Māori boilermaker on an outback construction job.

Despite Mason’s lofty praise, ‘Monologue’ feels like one of the few moments in the collection where these working-class concerns crystallise. The poem begins and ends with the speaker saying that they like ‘working near a door’, a motif that represents the instability of their work – they work near the door because they could be ‘out the door’ at any point:

I have worked here for fifteen months.

It’s too good to last.

Orders will fall off

and there will be a reduction in staff.

More people than we can cope with

will be brought in from other lands:

people who are also looking

for something more real, more lasting,

more permanent maybe, than dying . . . .

Writing about the later poem ‘Hotere’, Anna Jackson states that ‘there is a power […] to [that poem’s] rising inflection, a confidence in [Tuwhare’s] own vernacular, a pleasure in conversation that the conversational rhythm reflects.’ While ‘Monologue’ isn’t quite ‘there’ yet, it’s arguably the moment where Tuwhare seriously started to experiment with the blunt conversational wit that would become a key feature of his best poetry.

I could say something similar about ‘The Girl in the Park’, which was first published in a 1960 issue of the journal Mate, and is probably my favourite early Tuwhare poem. Like ‘Monologue’, ‘The Girl in the Park’ has a defined ‘character’ at its heart, and it’s clear that Tuwhare, at this early point in his career, worked best when trying to capture the voice of everyday people. The poem is a perfect blend of lofty imagery and almost child-like observations:

The girl in the park

saw the moon glide

into a dead tree’s arms

and felt the vast night

pressing.

How huge it seems,

and the trees are big she said.

There’s something evocative about the poem’s central image: of a young girl (but not that young, as she has a ‘lover’) standing, ‘moonrise and madness in her eyes’, beneath the vast universe. There’s something charming about the crafting of such beautiful images, followed by statements like ‘the moon is big, it is very big.’ And there’s the juxtaposition between the dark natural world and the girl’s wide-eyed wonder. I also like the uneasy relationship between figurative and literal imagery: ‘The girl in the park saw a nonchalant sky shrug into a blue-dark denim coat’ feels metaphorical, but ‘The girl in the park did not reach up to touch the cold steel buttons’ feels oddly literal, like the sky’s coat could be touched if she wanted to. I could say something similar about ‘Time and the Child’ - from earlier in this collection - in which an old man (representing time) is followed and called after by a precocious child: ‘funny man funny man funny old man funny’.

This sort of casual overlap between the physical and metaphysical worlds is similarly a feature of ‘Prelude?’ Once again, this poem feels like Tuwhare moving into his own style; a man dies and his soul emerges from the body, but there’s something strange, even comedic, about its construction. Even the title – the placing of a question mark after such a generically-traditional name for a poem – feels cheeky. As does the stark description of the man’s death:

Suddenly

He felt tired

Lay down

And died.

Tuwhare also has fun with the juxtaposition of the soul’s emergence and the mundane details of the death scene:

[His soul] Gave no heed

Nor feather turned

To the shocked cry

Heart-wails

The shattered tea-cup

And milk

Spilling on the floor.

I am reminded of Tuwhare’s later works that make the mundane fantastical, or the fantastical mundane (like ‘Study in Black and White’, in which a man comes into possession of a penguin). The metaphors in No Ordinary Sun can be more traditional, however: the roads in ‘Roads’, Old Man Time in ‘Time and the Child’.

And of course, there’s the tree in ‘No Ordinary Sun’:

Tree let your arms fall:

raise them not sharply in supplication

to the bright enhaloed cloud.

Let your arms lack toughness and

resilience for this is no mere axe

to blunt, nor fire to smother.

It’s difficult to find new things to say about this poem. ‘No Ordinary Sun’ is the most famous Tuwhare poem, and it’s the most widely taught in schools by far. And to be fair, it’s a classic: a romantic address to a tree that humanises it in opposition to the inhuman threat of nuclear warfare. And yet, there’s something unsatisfying about one of our best poets being reduced to a single poem – particularly one of his very earliest works. As a teacher, I see this happen a lot to Māori authors (how exactly did ‘Sad Joke on a Marae’ become the one Apirana Taylor work that most people will ever read?) and it tends towards an extreme focus on pieces that are serious takes on social issues. Such literature is important, of course, but many people might never realise how varied, how experimental – and just downright strange – an author like Tuwhare could be. Frank Stewart puts it nicely:

But the best description of Hone Tuwhare’s poems may be that they are not so much a collision of language as the luminous weaving of voices in rich conversation – lyrical talk between the reader and a joyful, exuberant man of many facets and many experiences…

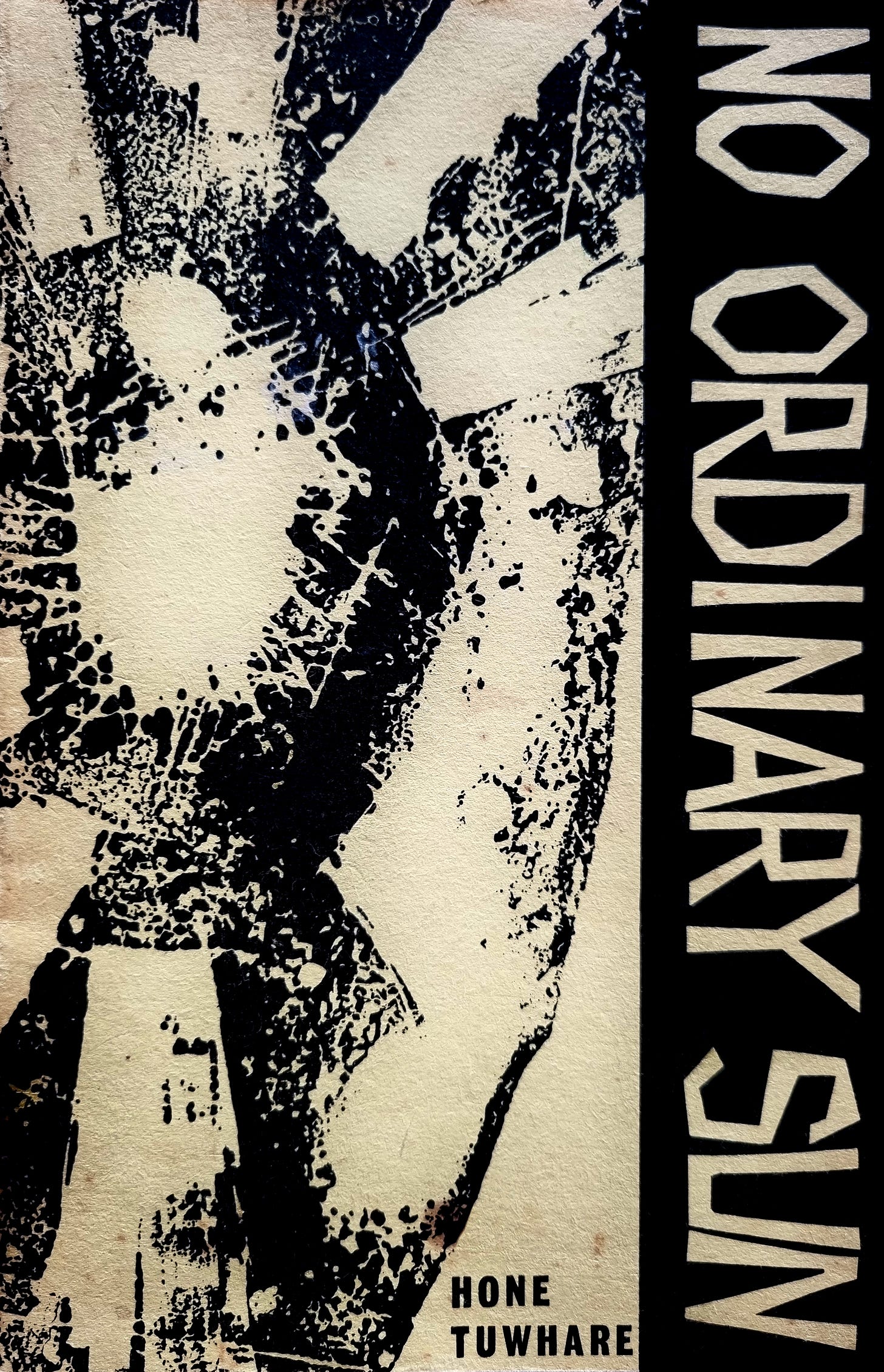

If you’re after that version of Tuwhare, No Ordinary Sun shouldn’t be your first stop. In many ways, the collection does feel like an antique (a beautiful one though, with a striking cover by Warwick Bradshaw). But there are interesting poems here, and plenty of moments where one can see flashes of Tuwhare’s future sparks.