At the end of this month, Patricia Grace is releasing a new collection of short stories: Bird Child and other Stories. Any new work by Grace is an event, but her short fiction continues to occupy a key space in the imagination of Aotearoa readers and writers. Patricia Grace short stories were some of the first works of Māori literature to ‘mean something’ to me, and I’m not alone in that experience – her early work is, to this day, the Māori writing most likely to be taught in classrooms across the country. My journey through the world of Māori literature can be traced back to the moment when – looking for something short – I picked up a collection of Patricia Grace short stories.

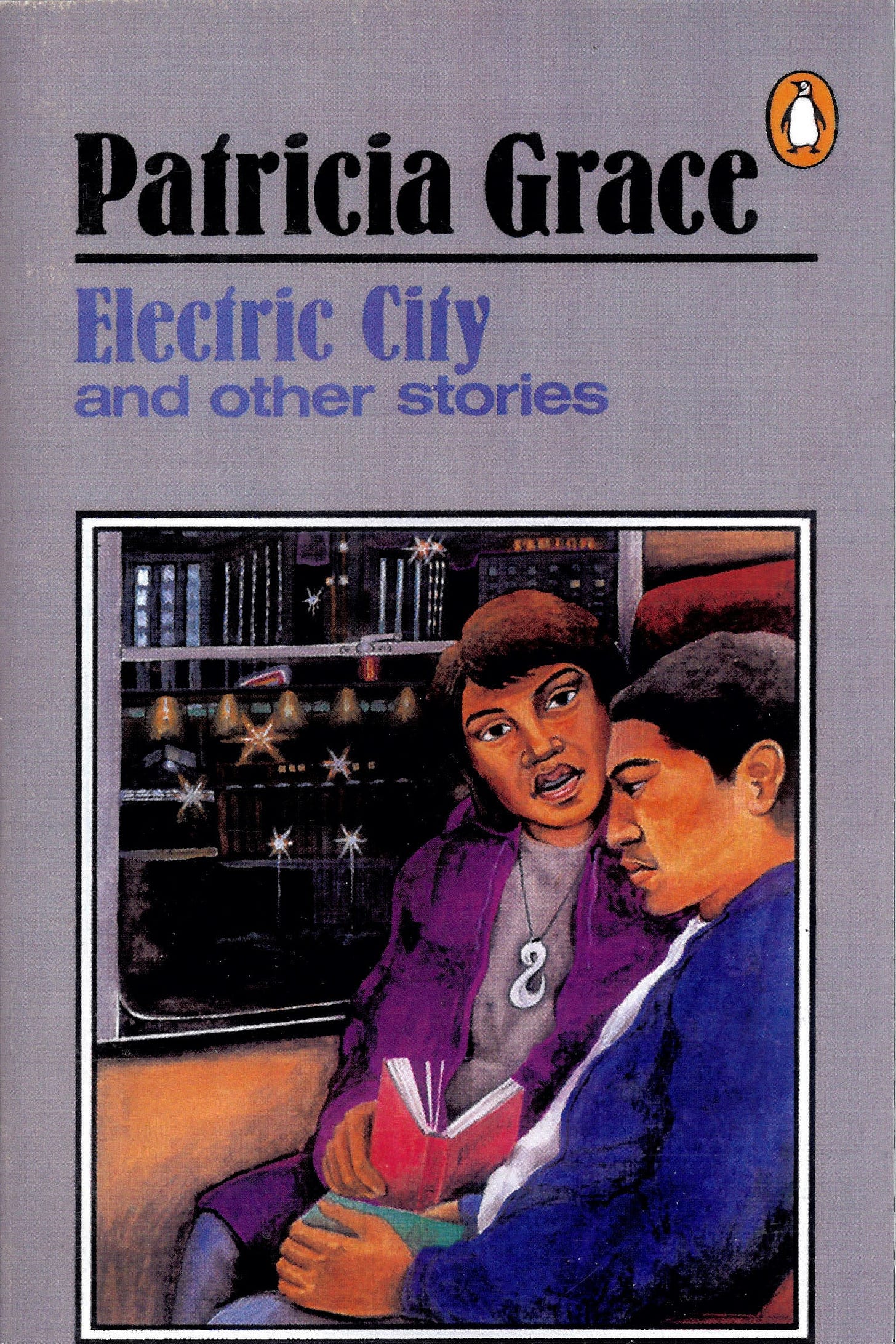

Electric City and Other Stories [1987] is her third collection of short fiction, and one could argue that it is her most iconic work. Electric City contains almost all of the Grace stories that one is likely to study at school: namely, ‘The Hills’, ‘Butterflies’, ‘The Geranium’ and ‘Going for the Bread’. The cover is a sleekly-designed Robyn Kahukiwa classic:

Shout-out to whoever at Penguin made the call to reprint this collection with art intact.

Unlike many younger readers who fall for Grace’s work, I wasn’t a secondary student but a university student. I had somehow made it through thirteen years of schooling still thinking that the literature of Aotearoa was – to be blunt – ‘boring’. To me, local fiction was the sort of thing that you read in class, but not outside of it. Worst of all, it seemed like it just wanted to teach me things; studies of Aotearoa fiction felt more like Social Studies than lessons in literature.

I think this is what initially attracted me to ‘Electric City’, the title story of Grace’s third collection – along with how tiny it is, amounting to only 550 words. This is Grace at her starkest, most stripped down: a brief coming-of-age story that feels uncertain and elusive, not didactic. The story is simple. Ani comes home after paying the ‘electric city’ (what the ‘old man’ calls the power bill), and soon heads off to an evening job with her brother Harry. They joke about their ‘old man’s obsession with paying the ‘electric city’: ‘he has everything counted out, this for the power, this for that, this for such and such, and such and such . . . like it’s his life.’ On the train, Ani studies, and Harry reveals that he skipped school to interview at a video shop; he plans to leave school and work full time to support the family. As the train emerges from the cutting, they gaze at the darkening city:

There were lights threaded about the harbour, and layers of light patterned the sides of the tall buildings. Beside them on the motorway the headlines of hundreds of cars beamed on to the darkening roadway.

‘So it’s right,’ Ani said, ‘It’s what he means.’

‘Electric City,’ Harry said.

The train shuffled into the station and they looked out into the long, lit-up shelters under which commuters waited, hunching against the cold.

‘Electric City,’ she said. ‘And you always have to pay.’

Grace has always been political, never shying away from making clear statements when appropriate. Much of her best work, however, revels in doubt. See ‘Parade’, from 1975’s Waiariki and Other Stories, where a character fears that their ‘cultural’ parade float reduces Māori to a tacky performance; another character responds that even imperfect ‘performances’ provide essential visibility – a complex issue, and Grace sees no need to resolve it. My initial response to ‘Electric City’ was similarly complex. The story concludes with an evocative image – two teenagers witnessing a city bursting into light – and it feels like a moment of realisation; but of what, exactly?

Now I like to think of Ani and Harry becoming aware of the constant pressure of capitalistic society, of their assimilation into the system that – embodied by the twinkling cityscape – spreads out before them. Perhaps they realise that the old man’s restlessness about the ‘electric city’ is not unfounded. It’s fitting that such a concise story feels similarly restless in its pacing; time in ‘Electric City’ is completely governed by jobs, routines, money. Ani is introduced after paying the power bill; her and Harry have to ‘scoff’ a dinner; they’re too late to cook for Pania; Ani has to study on the train for tomorrow’s test; they hope that their evening shift won’t make them miss the (extremely specific) two-to-nine train home. The pace is suffocating, and it makes the final moment of contemplation land hard.

But there’s also something about ‘Electric City’ that’s harder to put into words. It has the quality that simple, sparse storytelling sometimes has (when done well). There’s so little on the lines that what might lie between them becomes especially alluring – there’s something not being said here. ‘The Geranium’ – also from Electric City – has a similar quality: a story about domestic violence that is particularly devastating because it barely mentions it. ‘Electric City’ has a spectral unease at its core, capturing the broken lives of this urban whānau with ruthless efficiency. Ani and Harry – the one relationship in the whānau actually depicted on the page – feel fated to drift into their own corners of an inhospitable society.

She’d soon produce arguably her most ambitious work in the sprawling Cousins, but Electric City and Other Stories is the Patricia Grace I return to most. The strongest pieces here – like the title story, ‘The Geranium’, the incredible ‘Hospital’ – are the purest, clearest examples of Grace’s storytelling craft, and I’m excited to see what Bird Child and Other Stories adds to this legacy.

This kōrero has inspired me to read this one! Ngā mihi for your wonderful words 🩵

beautiful mahi ❤️❤️❤️