The Auckland Central City Library is currently holding an incredible exhibition called Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu (Speak Eloquently) which aims to celebrate the writing and expression of te reo Māori from the early nineteenth century to the present day.

The exhibition features a range of taonga that represent the development of written te reo since the 19th century. What’s especially exciting is that Damien Levi, Library Publishing Specialist, has worked to assemble a zine in response to the exhibition.

I was lucky enough to have an essay featured in this zine, alongside writing by Nicola Andrews, Elise Sadlier, and Daniel Taipua.

Here is the essay I wrote in response to Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu, titled ‘Those Who Speak Eloquently’, alongside some photos I took of the exhibition.

At the 2023 Verb Readers and Writers Festival, I was invited to speak alongside the incredible Matariki Williams for a session called Our Māori Archivists. Facilitated by Trinity Thompson-Browne, the kōrero was great, but it undoubtedly reinforced a feeling I’ve had for a while: that what I do—working with Māori fiction, poetry, theatre—doesn’t feel like ‘research’ to me. Yes, that event generously described me as a researcher, but I’m not. This might sound like coy self-deprecation (and I’m definitely not above that) but I think it’s more to do with a distinction between the comfortable world of literature intended to reach a wide audience, to transcend the limits of its contemporary readership, and literature that was not.

To put it bluntly, I don’t have to dig my books out of archives or collections; they’re sitting in bookshops.

I thought about this distinction again while viewing Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu. Translating to ‘speak eloquently’, the phrase titles an exhibition at the Auckland Central Library that celebrates the writing and expression of te reo Māori from the early nineteenth century to the present day. The exhibition is contained within a single dimly lit room (for preservation purposes). Cabinets contain various taonga of the Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, each a key moment in the ongoing story of written te reo: hand-written recordings of kōrero tupuna, grammar books, student workbooks, and other pieces.

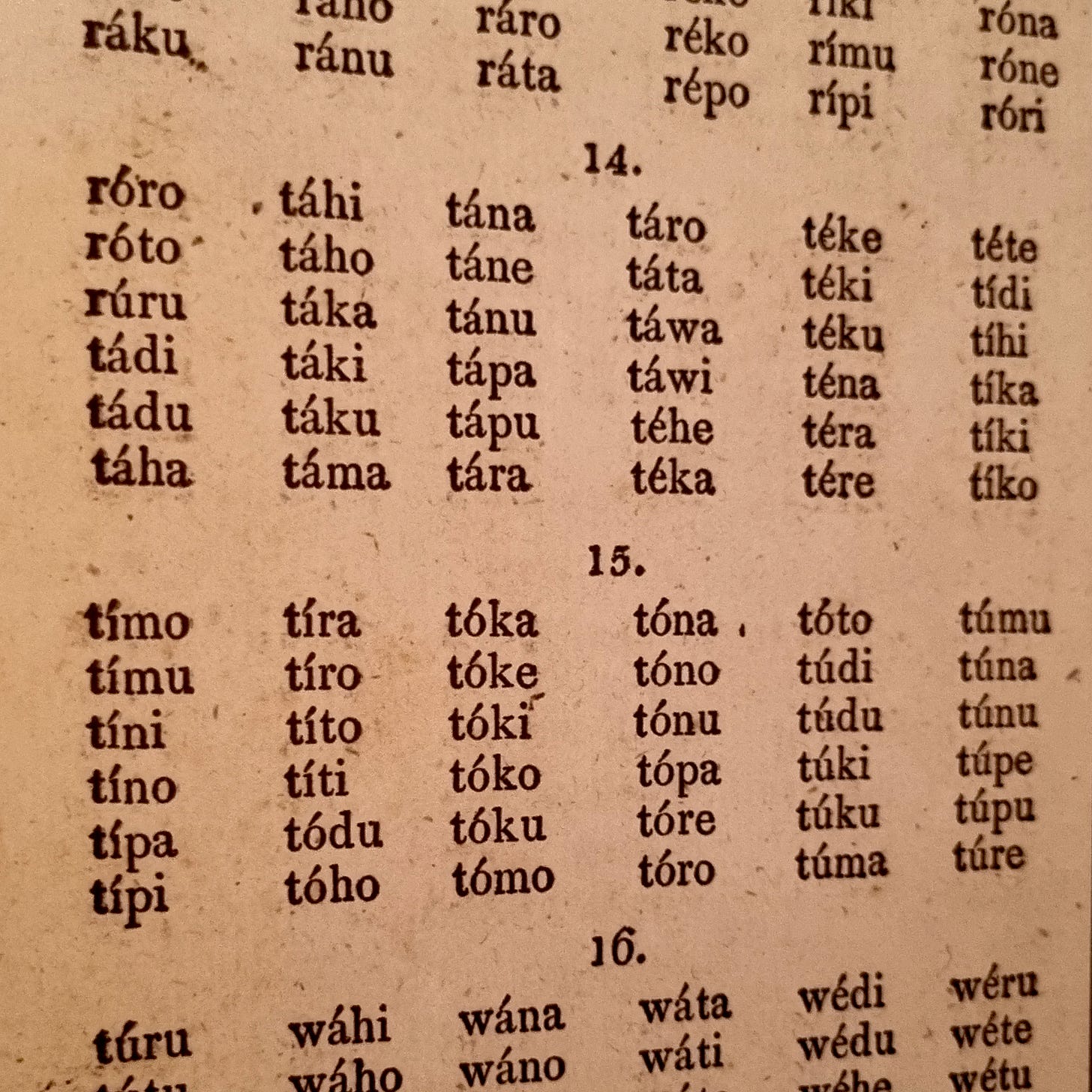

For someone whose love of Māori creativity generally comes in the form of English-language fiction and poetry, there’s something confronting about the collection’s works of te reo Māori—particularly as I lack the proficiency to meaningfully engage with all but the very simplest texts. And it’s not just the reo that makes Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu challenging to respond to; it’s also the stark presentation of so many of these taonga, with text filling entire pages—either hand-written or printed—and little in the way of useful markers for unfamiliar readers. This of course makes reading these works very different to reading, say, a poem. Poetry is beautiful, but it knows it’s beautiful. A poem wants to be read closely and allows itself the space on the page to be taken slowly and seriously—a very different experience to reading a page thick with handwritten reo.

The collection and supplementary assembled for Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu resources – particularly the Ngako: The Collections Talk video - are, thus, vital to allowing a reader like me access to the beauty of these items. And the exhibition makes sure to place focus on beauty, on the eloquence of these taonga. The walls are filled with the art of pukapuka, the kind of stuff that I love and collect (where possible): the illustration work of Kāterina Mataira’s Maui and the Big Fish, Dennis Turner’s melancholic, monochrome Tangi, a soft watercolour painting of Hinemoa and Tūtānekai by Richard Aldworth Oliver. Even though I didn’t grow up with this stuff, I feel at home amongst these, and it’s great to see some things I wasn’t already familiar with—like John Stinchcombe’s lively (even downright kitschy) covers from te reo versions of Goldilocks and Jack and the Beanstalk. But most surprising is the way in which the exhibition and accompanying soundscapes illuminate the artistry of the less accessible taonga.

See, for example, the way in which Xavier Forsman talks about a dense page of text extracted from Te Korimako, an 1880s Māori newspaper, explaining the metaphor of its title. Korimako is a bell bird, and bird names were commonly paired with newspapers of the era. However, Forsman also draws on a tau: whakarongo rongo ake ki te reo o te manu e tangi mai nei huia, huia, hui, huihuia—“Listen to the call of the huia bird as it cries out.” “Bird calls in Māori,” he explains, “are often expressed as being like knitting or sewing. So, the call of the bird unites people.” It strikes me how Forsman highlights a passage amongst the vast columns of text and praises the beauty that I would have otherwise passed over: “ka hukapapatia ngā tangata e ngā kupu mātao, a wera ana te tangata i ngā kupu pāwera, a kawa ana te tangata i ngā kupu kawa, a ko ngā kupu riri, hei whakatupu i te riri.” He elaborates on its meaning, saying that the passage addresses how “words of a certain nature beget the feelings that are associated with them”—‘cold’ words inspire feelings of cold, for example.

It is fitting that the full expression from which this exhibition gains its title goes on to not only suggest that we ‘speak eloquently’, but that we should also ‘keep it simple and beautiful’. Most of what is contained within Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu is what some might unwittingly disregard as ‘functional’ writing: texts designed to serve a specific purpose in a specific time and place. How many of these authors would have imagined their words finding this audience in this strange century? But it’s this focus on ‘functionality’ that makes these texts surprising in their moments of often-incidental beauty. That is, the repeating, looping handwriting of a student trying to master the written form of their language, or pūrākau fanning across a page in waves, shaped like a tokotoko, designed specifically for memorisation. Here, ‘function’ naturally encompasses pattern and metaphor with both simplicity and beauty. As Raniera Kingi notes in his explanation of a book of popular Māori songs, contemporary orators continue to seek out traditional karakia for their brevity. “They were,” he argues, “not very long winded”—even to one without the requisite reo, this quality is apparent simply from their presence on the page.

And yet, there’s an unknowability that pervades many of these taonga, particularly when one thinks of the relative wealth of knowledge that surrounds the Māori literature of the second half of the 20th century. There’s something evocative, for instance, about the double-page spread of an exercise book filled with two repeating phrases: “Pai rara te korero o te Atua” on the left-hand side, and “A very naughty Boy” on the right. The first phrase is obviously reflective of how writing lessons would converge with religious instruction, but the second phrase can only remind me of some sort of punishment—is this an example of a student ‘writing lines’?

I was similarly drawn to a large display of a familiar image, a 1908 photograph of Karioi Native School’s infant class. It’s a famous image—you can find it on Te Ara’s entries about the development of te reo Māori. The black-and-white image has an unnerving quality. A stern-looking teacher stands at the back of a room while eleven unsmiling students hold up slates, each containing an odd combination of chalk drawings: a fish, a snail, and what appears to be a bunch of grapes. It’s hard to know exactly how anybody felt in that classroom at that particular moment in time—nor what the photographer was hoping to convey through their art. And I’m aware that it’s especially easy to view these works through a 21st century lens coloured with a modern understanding of the ills committed against tamariki Māori by New Zealand schooling institutions. I can’t know these works in the same way that I can know modern works of Māori literature; as a result, they feel unsettling. They force me to question my gut reaction, to seek further context, and reach for the expertise provided by the overall project of Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu.

There’s something humbling—perhaps even vulnerable—about reading and responding to an exhibition like this that is (for the most part) completely out of my comfort zone. Reviewing a novel is different; it’s generally enough to bring yourself to it. Even the most esoteric novel sits on a bookshop shelf and wants to be bought and read. Here, I am reliant on what Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu provides. And what strikes me most about these offerings is how little they trade in dusty terms like ‘importance’. These taonga are essential moments in the development of written te reo, but I love the way in which these experts approach them with aesthetics at the forefront. They unfurl these pages with aroha, carefully translating their moments of poetry. Even a page of repeated writing exercises gets praised for the student’s sleek penwork. You should try and engage with these works in the library’s collection, and yes, the ‘importance’ of these works is a big part of why you should. But I encourage you to spend the time listening to what Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu has to say about how each one brims with its own lyricism and life.

I don’t speak te reo Māori, but I know that I will one day. So often these sorts of statements are tinged with sadness, with the dark history of how our language became something that needed to be reclaimed. One’s reo ability (or lack thereof) is commonly viewed through a lens of shame. I do not wish to downplay these experiences; they are very real. And yet, Waiwaia Ngā Ngutu feels to me like a reminder that there’s something exciting about this—that the reclamation journey will also be about finding one’s place within a sprawling whakapapa of writers and artists whose mahi has made the opportunity possible. More importantly, it will be about the discovery of language and its inherent beauty: the eloquence contained within each of these cabinets. Did that student with the nice handwriting get some sort of joy from learning to put those phrases to paper for the first time? I’d like to think that he did.

I can’t help but view an expansive, impenetrable page of Te Korimako as the perfect representation of how much I have to learn when it comes to our reo. But seeing someone lovingly pore over it to extract a surprising moment of poetry—this feels like a reminder of why it’ll be worth it.