WAHINE TOA: WOMEN OF MAORI MYTH

The 1984 mythological collaboration between Patricia Grace and Robyn Kahukiwa

Wahine Toa: Women of Maori Myth is one of many celebrated collaborations between Patricia Grace and Robyn Kahukiwa, and I was recently able to pick up a copy. I was immediately struck by how contemporary it feels; this is a collection that examines key mythological narratives from a distinctly Māori perspective, but it also focuses specifically on female figures. These approaches feel modern still, particularly when I think about all the not-as-old-as-you-might-think books about Māori mythology by non-Māori that I find in second-hand book shops (these can still have their own appeal, of course).

The other striking thing about Wahine Toa is that despite being a book with words and pictures, it feels more adult in length and tone. In fact, Kahukiwa even mentions this as a core concern of her paintings here:

I […] wanted my work to be relevant to adults because for too long Maori mythology has been reserved for children only, and I am sure the myths provide something for everyone if he or she will take the time to read or listen to them. As Joan Metge (1981) has written: ‘The tremendous power of myths to survive and to move men lies in the fact that they deal ultimately not with particular social orders but with problems that confront all men, whether simple societies or complex, with the problems that are rooted in the human condition.’

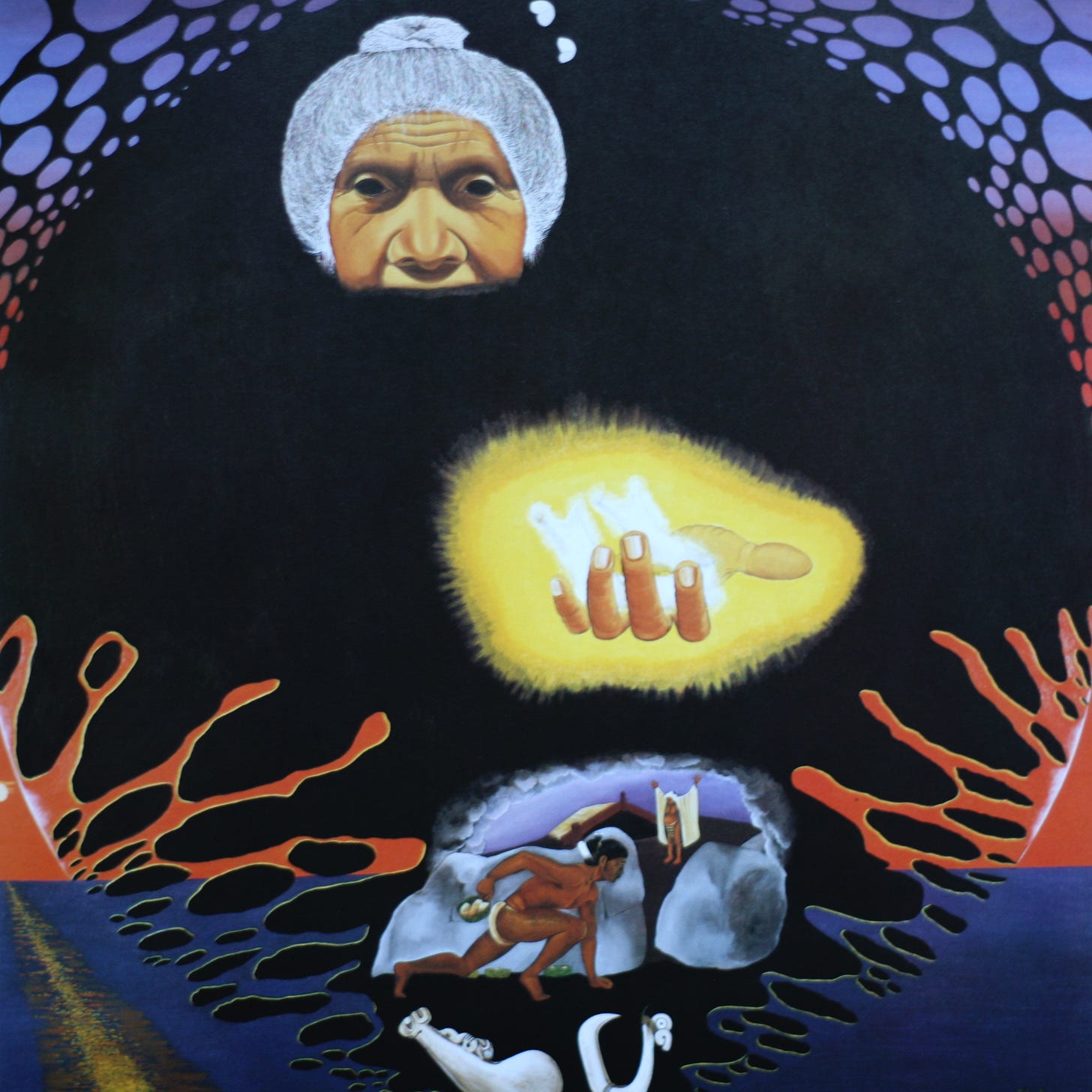

Kahukiwa’s series of paintings (and accompanying drawings) aimed to ‘redefine’ eight mythological narratives, and the idea was later introduced to combine them with writing by Grace to produce a book. Like the original exhibition, Wahine Toa is divided into eight sections: ‘Te Po’, ‘Papatuanuku’, ‘Hine-ahu-one’, ‘Hine-titama’, ‘Taranga’, ‘Mahuika’, ‘Muriranga-whenua’, and ‘Hine-nui-te-Po’.

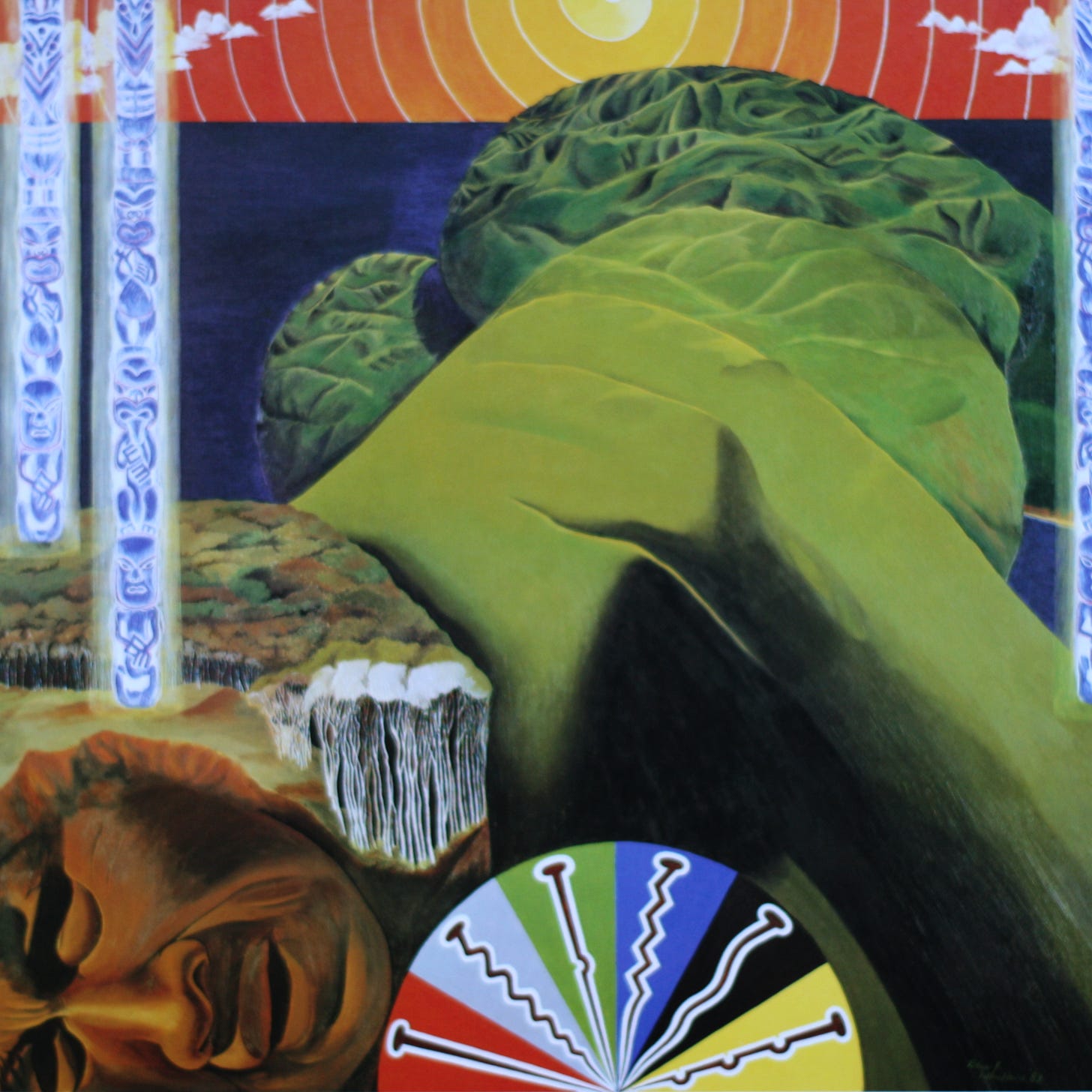

In her foreword, Kahukiwa explains that each painting is not merely an illustration of the myth, but an attempt to embody the entirety of its narrative. This ambitious approach distances Wahine Toa from many earlier attempts to visualise these stories, and also results in dense, evocative paintings that combine literal and figurative imagery.

In one painting, for example, we see Hine-nui-te-pō with legs open and Māui in lizard form. And yet, we also see visual elements that are not immediately clear on a literal level: a foetus, which Kahukiwa mentions as representative of humankind, and a kowhaiwhai pattern called ‘Māui’.

I get the sense that Grace was aware that the beauty and symbolic value of Kahukiwa’s paintings would be worth the price of admission alone. As a result, her writing feels relatively stripped back and unobtrusive. There are, however, some nice touches that reflect what was happening in her short fiction of the era, like her love of repeating, hypnotic phrases:

I am aged in aeons, and I am Night of many nights. Night of many darknesses – Night of great darkness, long darkness, utter darkness, birth and death darkness; of darkness unseen, darkness touchable and untouchable, and of every kind of darkness that can be.

It’s interesting revisiting these concise one-page pieces after reading Grace’s latest collection Bird Child and Other Stories. Parts of Bird Child aim to re-examine pūrākau, and the style is so much more subversive and more concerned with the psychology of characters. Wahine Toa plays it fairly ‘straight’, for the most part:

Tane blew on me, my eyes opened and I drew breath. I sneezed and was alive.

But Tane’s searching was not yet over. He sought a way in which to combine our two elements – and so produce mortal life.

He searched my body, acting in its orifices. These first contacts produced earwax, tears, mucus, saliva, sweat and excreta. But it acting within my clitoral opening our male and female elements came together and Hine-titama was conceived.

Despite the first-person perspective, Grace’s pieces here are less concerned with exploring the morality and psychology of these moments. Rather, they serve to reinforce Kahukiwa’s art, which is obviously outstanding. And in between each writing/painting double-page spread, we get related pencil drawings that demonstrate Kahukiwa’s flowing, expressive linework.

Grace would revisit this sort of subject matter later in more interesting, subversive ways, but Wahine Toa: Women of Maori Myth remains something that you should get your hands on if you can. I imagine it’s one of the easiest ways to see these paintings with this level of quality, and Grace’s contributions are good, if a little reserved. On a broader level, it’s another example of the close connection between art and literature in te ao Māori.

wow, Jordan. Your write up is so inspiring. I am going to try to find my own copy (hen's teeth?)