Within the various literary circles of Aotearoa, it has been common to – for various reasons – separate out Māori and Pākehā literature into two distinct strands. However, both literary histories are connected in at least one facet: a relative lack of major works of speculative fiction. In an essay on M.K. Joseph’s overlooked science fiction, Jack Ross attributes this lack to economic realities: ‘Our writing has tended to be ‘literary’ because we lack a mass audience of consumers […] [works of genre fiction] have to compete for attention with the same small stock of book readers and buyers.’ Our lean towards stark social realism was described allegorically by Roger Horrocks in the early 1980s:

One day out in the back of beyond you come across a small town, run-down because many of its young people have headed for the city. In an unpretentious building you discover a local art gallery-cum-museum. A solitary caretaker puffing a pipe turns on the lights and you are startled by the paintings on the walls... Here are old images of heaven and hell that now have a surreal air. You'd like to understand this odd iconography but the caretaker has a curiously literal approach - he tells local stories about the paintings as though he were pointing things out to you through a window.

One result of this anti-speculative bent is that both Māori and Pākehā writing has never really crafted a coherent futurism. We have quality works of speculative fiction – and plenty that submit visions of the future – but it doesn’t stack up against the ease with which most people can imagine futures in other parts of the world, with their wealth of dystopian, cyberpunk, post-apocalyptic (etc.) literature. What sort of future might represent Māori hopes and fears, and more importantly, what does that look like in our fiction?

For this reason, I’m always looking out for works of Māori futurism, and my recent favourite comes from an unlikely source: Umurangi Generation, the 2020 indie photography videogame developed by Australian-based Māori creator Naphtali Faulkner. The game is set in a future Tauranga, in the midst of some sort of near-apocalyptic scenario that never quite makes itself clear within the ‘narrative’ (if you can call it that). There’s giant mechs, aliens of some sort, United Nations forces, and young Māori protagonists viewing it all from afar. It’s all brought to life with a jaggy 2000-era look that evokes games like Jet Set Radio.

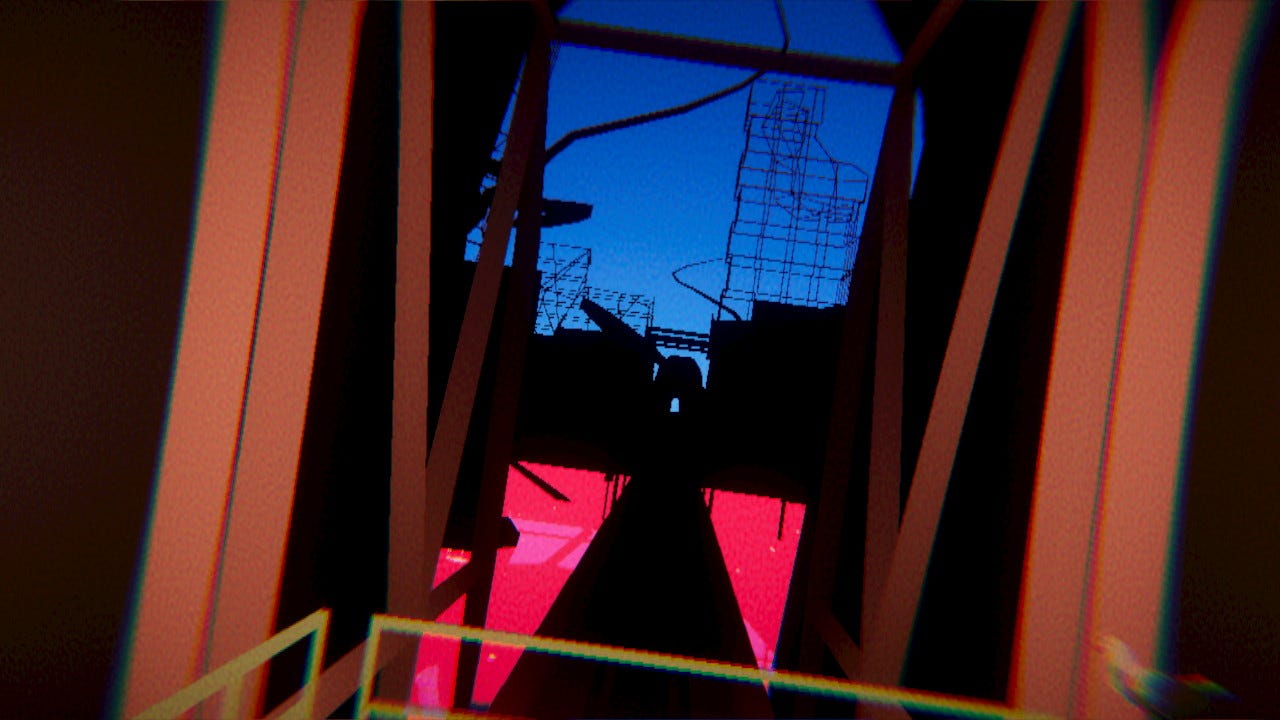

As a gamer who was born in 1990 and still regularly listens to the Super Monkey Ball 2 soundtrack, this is right up my alley. Modern gamers are spoiled by seamless, impossibly-detailed open worlds, but these same modern trends have also amplified a nostalgic desire for the hazy, disconnected dreamworlds of early 3D gaming – when technological limitations meant that any ‘sense of place’ was really just some textures wrapped around some low-polygon boxes. Umurangi Generation’s level design embraces these aesthetics; its structure is downright arcade-y, and its idea of immersion is to drop the player into some new corner of its ambiguous dystopia.

But these choices aren’t just nostalgia bait for backwards-looking aging gamers; they’re essential to what I find so compelling about the game’s futurism. See, I’ve always had this hope that one day something comes along and delivers some huge artistic – and aesthetic – statement regarding Māori futurism: a kind of Māori Neuromancer that somehow defines a genre in one swing. Umurangi Generation isn’t that, but that’s what I love about it. It’s intentionally fragmented and ill-defined – and really, isn’t that the most fitting representation of where our thinking is right now? My social media feed talks about the far future more than what is probably healthy, and it’s always swaying between blue-sky solarpunk hope and dead-end dystopia. No one really knows what to expect anymore, and one could argue that indigenous people occupy an especially precarious place in all this.

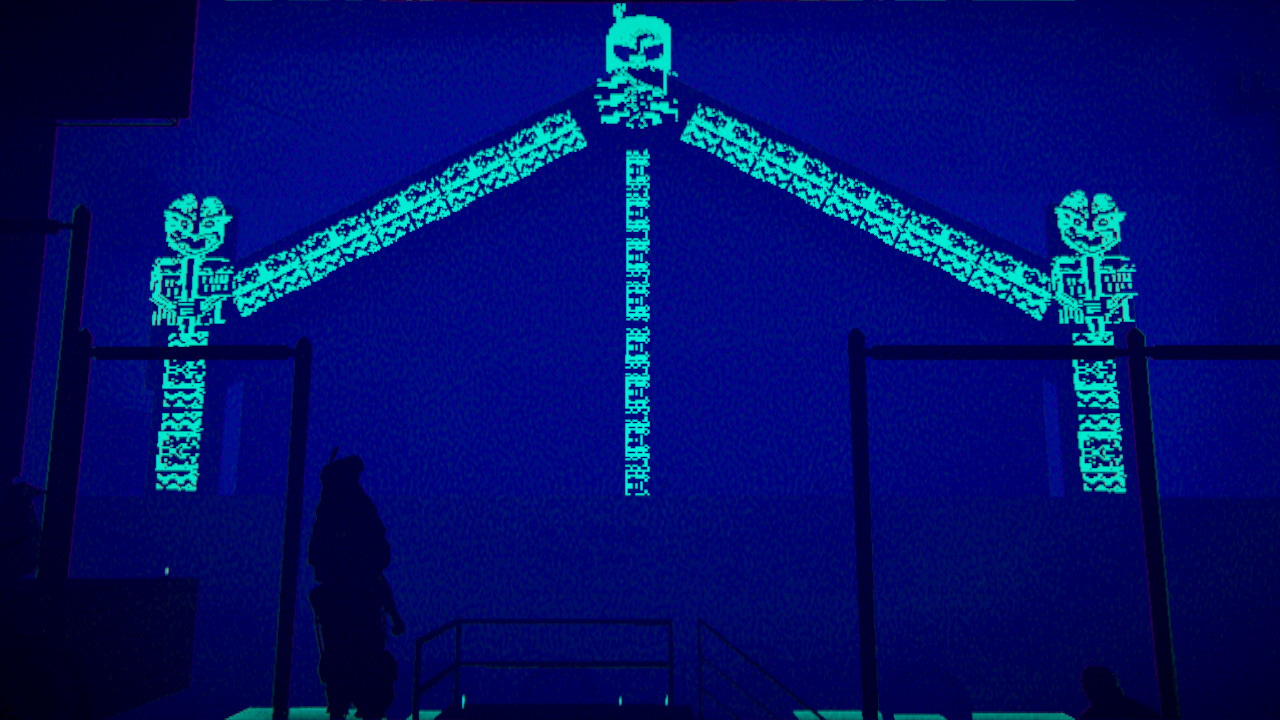

And so Umurangi Generation’s world-building simply deals in a series of evocative images (fitting when that’s also the main gameplay mechanic), rather than anything that feels truly cohesive. It’s a future made up of lurid, disconnected moments in time (which is basically what my own vision of it tends to be): the level where a train is shuttling across a red sea between twisting ruins, the level where a neon-fringed wharenui emerges from foggy city streets, the level where you stand on a dark rooftop while a Lovecraftian entity hangs in the sky. It turns out that a photography game sort of in the vein of Pokémon Snap is the perfect vessel to tell a loosely tied story about rangatahi Māori navigating a future that is being guided by forces beyond their control.

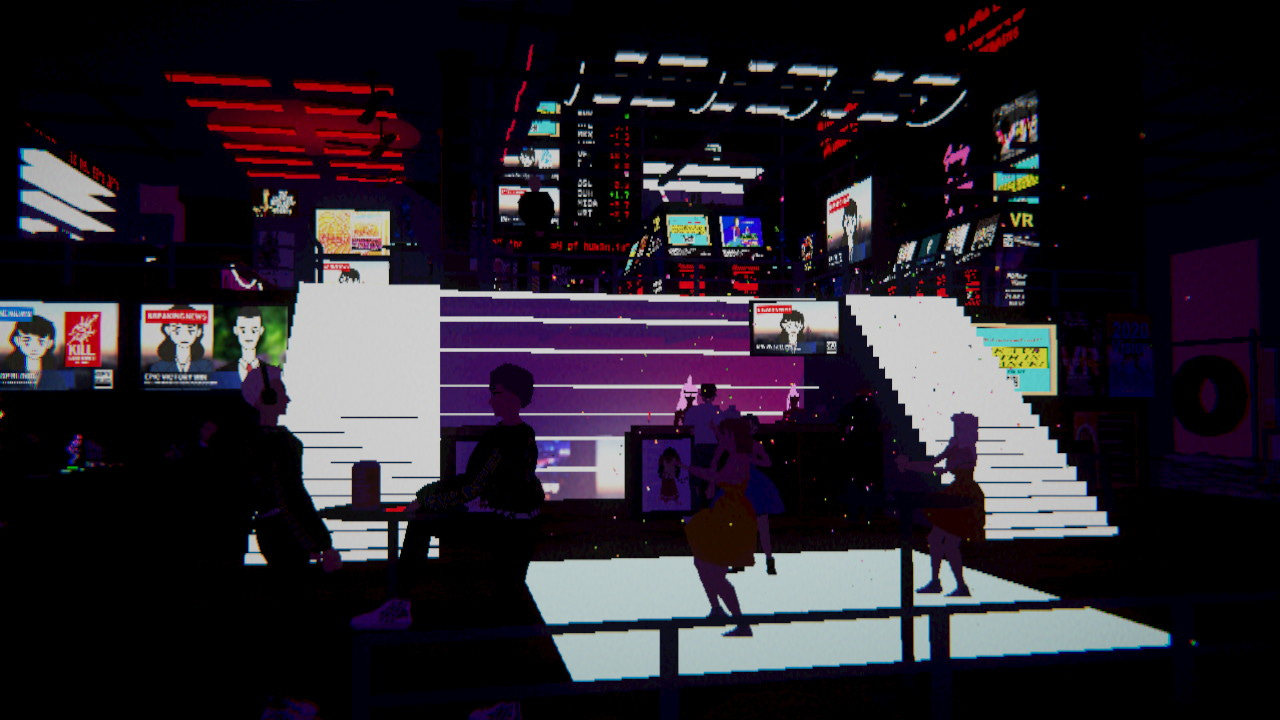

And yet, its action isn’t simply about passive observation. There’s a countercultural, rebellious streak that is mostly presented through environmental details. You get the sense that youth culture is being fostered at the outskirts of future-Tauranga, down in the dingy streets while the giants do battle above. Even the main gameplay mechanic – in which the unnamed player is tasked with photographing each level – feels like meaningful action. Yeah, you’re mostly just taking photos (and the levels are, compared to similar games, mostly non-interactive) but I love this notion of using a camera to wring small pieces of beauty out of a world approaching annihilation – and even though the main game is guided by specific tasks, just trying to make something that looks good on repeat plays becomes its own reward. When discussing gameplay incentives, Faulkner has noted the importance of ‘[making sure] that players aren’t conditioned to be creative how [the game] thinks they should be.’

But there’s an undeniable hopeless streak to Umurangi Generation, which was inspired in part by the apocalyptic imagery of the 2020 Australian bushfires and the government’s limp response. Faulkner classifies the game as ‘shitty future’, and the recurring motif of huia feathers firmly foreshadows an extinction-level event. The main game’s final level takes place at the Bowentown heads, where the only task is to inch your way towards one final image: the silhouette of a cosmic horror monster against a red sky, observed by ghostly cloaked figures that line the shore. It makes sense that your avatar stands alongside their tīpuna in the end; this is a world where every aspect of society has crumbled, except it would seem, the community of indigenous people. And all you can do at this point is photograph the monster.

The game ultimately presents an ambiguous, disconnected futurism, but it completely justifies it. In fact, Faulkner has voiced dissatisfaction about speculative movements that are too entrenched, such as the cyberpunk genre that the game arguably falls into:

I'm kind of frustrated with cyberpunk as a genre at the moment because it is so much aesthetic over thematic at this point," Faulkner says. "For the last ten years, it's been very much cyberpunk as an '80s circle jerk.

A quick look through any #cyberpunk tag will make it clear that that particular movement has stagnated aesthetically and has been cut loose from its radical political associations. Umurangi Generation highlights the potency of a futurist movement that has yet to be clearly defined – that is, we can do whatever we want, free from expectations of ‘the genre’, and craft futurist narratives as fluid and uncertain as the future itself.

I've been meaning to play Umurangi Generation and write about it for a long time.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

Very cool, loved the close read. Just found this on Steam. Gonna have to check it out!